What the 2025 Nobel Prize in Economics Teaches Us About Innovation, Part 1: The 3 Prerequisites for Sustained Growth

By Mike Rainone

This year’s Nobel Prizes have been announced, and the one that caught our eye is not the prize in chemistry or physics or even medicine, but economics.

The 2025 Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences went to Joel Mokyr, Philippe Aghion, and Peter Howitt, for their explanation of “how innovation provides the impetus for further progress.”

Essentially, their work not only proves the value of innovation on a large, global scale but also details how innovation takes place. This isn’t just academic theory; it’s a blueprint for understanding the very forces you’re trying to harness.

So let’s take a closer look at these economic theories, starting with Joel Mokyr, to uncover what lessons you, as an innovator, can take away from them.

The Phenomenon of Sustained Growth

Joel Mokyr received one-half of this year’s prize “for having identified the prerequisites for sustained growth through technological progress.”

Mokyr, an economic historian and professor at Northwestern University, is unique among his peers in that he has a surprisingly optimistic outlook. As he said recently at a Northwestern symposium, “The last 150 years have been absolutely miraculous in the history of the human race. The living standards that would have been unimaginable in the 1870s have been attained not just by the very wealthy and top layers of society, but basically, by regular citizens. The average life expectancy in the world today is 73 for women and 68 for men. In the 1870s it was in the upper 30s. We have doubled it. That gives you an indication of what we have achieved.”

This is one of the key findings of Mokyr’s work: the last 150 years are in fact quite unique in relation to a larger view of human history. It is only for the last 150 years or so that we have seen sustained economic growth. Prior to that, before the Industrial Revolution, growth was largely stagnant, despite major scientific and technical breakthroughs. For instance, the Enlightenment saw such developments as Isaac Newton’s laws of motion and universal gravitation and Benjamin Franklin’s experiments in electricity. Yet such discoveries did not lead to applications that led to sustained economic growth.

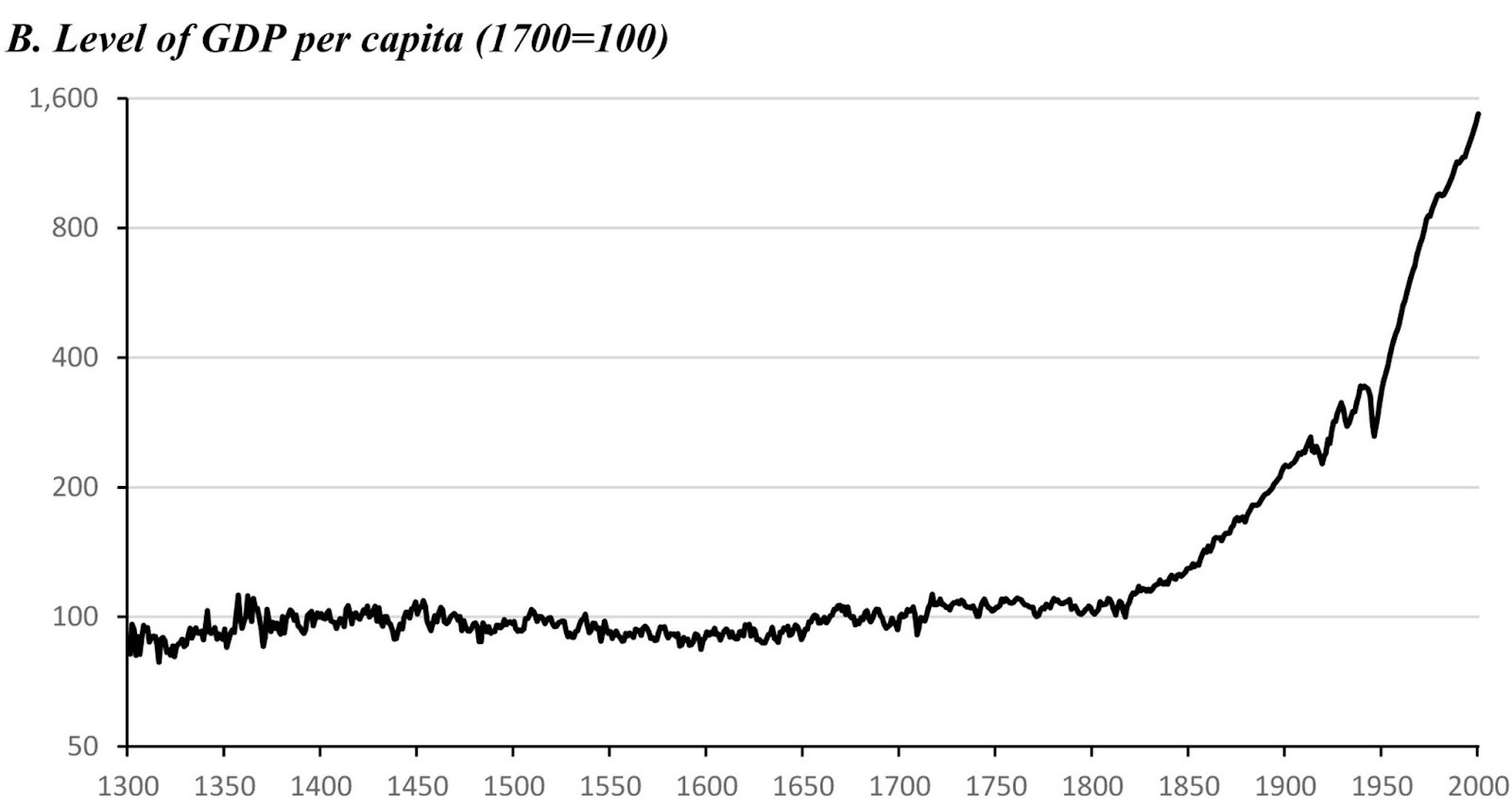

To visualize just how drastic this change in growth was, look at the aggregate GDP per capita for Europe from 1300–2000, from Stephen Broadberry and Jason Lennard’s journal article “European Business Cycles and Economic Growth, 1300–2000.”

What accounts for this change, and what keeps us on a path of continued sustained growth? This is the question that Mokyr answered, identifying three important prerequisites for sustained growth: useful knowledge, mechanical competence, and a society open to change.

#1: Useful Knowledge

Mokyr argues that “useful knowledge” derives from two types of knowledge: propositional knowledge, which is the knowledge of “facts” (or whatever is believed to be fact at the time) about the world, and prescriptive knowledge, which is how things work in practice. It’s an oversimplification, but you can think of propositional knowledge as the precursor to what we know as “science” and prescriptive knowledge as “technology.” Or as another simplified way to think of it, propositional knowledge is theory, and prescriptive knowledge is practice.

In early human history, there was a disconnect between propositional knowledge and prescriptive knowledge. As Mokyr wrote, it was “a world of engineering without mechanics, iron-making without metallurgy, farming without soil science, mining without geology, water-power without hydraulics, dye-making without organic chemistry, and medical practice without microbiology and immunology.” Often, people knew that something worked but not why it worked. Knowledge and understanding were limited, and so people lacked the wisdom necessary to be able to innovate effectively, with innovation after innovation driving sustained growth.

Beginning in the Enlightenment, this disconnect began to close. Propositional knowledge became more accessible to greater numbers of people, spreading from, in Mokyr’s words, “more arcane realms of mathematics and experimental philosophy to the more mundane worlds of the artisan, the mechanic and the farmer.”

Thus began an important feedback loop. Propositional knowledge influenced prescriptive knowledge, leading to the development of innovations. The technological success of such innovations then reinforced and increased confidence in the propositional knowledge, leading to yet more innovations and ultimately contributing to the sustained growth we’ve now enjoyed for so long.

The takeaway for innovators: Science and technology are intertwined. For sustained economic growth, scientific breakthroughs and university research must be translated into practical, commercial innovations. In turn, the success of innovations can potentially point researchers toward the most useful areas of study.

#2: Mechanical Competence

Mechanical competence refers to the ability of skilled workers to implement new technologies, putting them into economic use. These are people Mokyr calls “tinkerers,” “tweakers,” and “implementers.” They’re the ones who can translate abstract ideas into practical applications. I would argue that most innovators today fall into this category.

Mokyr distinguishes between “macro inventions” and “micro inventions.” Macro inventions are the major breakthroughs with no clear precedent that create entirely new industries or technological paths, like the steam engine. Micro inventions are the incremental improvements that build upon what exists to create something new and better, like James Watt’s separate condenser for the steam engine, which greatly increased engine efficiency and allowed the steam engine to be applied in more ways, like in ships.

While there have been macro inventions throughout history, Mokyr points to the micro inventions as key for sustained economic growth. A single macro invention will cause a spike in growth, a succession of micro inventions is necessary to sustain that growth over time. The tinkerers are often the ones who drive micro inventions.

The takeaway for innovators: Look for what already exists and find new, innovative ways to improve it or apply it in new areas. These so-called “micro inventions” are crucial to driving economic growth.

#3: A Society Open to Change

Still today, there is often widespread resistance to change—it’s part of human nature. In the past, though, such resistance was even more pronounced, typically driven by people with vested interests who oftentimes held (and wanted to maintain) monopolies on resources, formal skills, equipment, etc.

For example, in the seventeenth century, Galileo faced backlash from the Catholic Church for his support of the heliocentric model. In the eighteenth century, John Kay, the inventor of the flying shuttle for mechanized weaving, was harassed by weavers. And in the nineteenth century, the medical establishment vehemently opposed Ignaz Semmelweis’s proposition that physicians should wash their hands to prevent the transmission of contaminated matter.

Beginning in the Enlightenment, though, a “culture of growth” began to take hold. People and institutions both became more open to new ways of thinking, allowing for more and faster innovation.

A number of factors likely contributed to this shift in culture. I would personally argue that one of the most important is that the changes improved people’s lives, from their health and safety to the cost of goods to the experiences available to them.

The takeaway for innovators: Anticipate resistance. For your innovation to be adopted, it must provide enough value to overcome the pain of change.

From the Past to the Future

So what does all this mean for the future? Well, that depends on what we do with the information. As the economic sciences committee at the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences wrote in their scientific background report, “Economic stagnation, not growth, has been the norm in human history, and the role of science, innovation, and creative destruction cannot be overstated in the unprecedented economic growth experience since the Industrial Revolution.”

If we want sustained growth to continue, on a societal level, we must foster environments that support the generation and application of useful knowledge, cultivate mechanical competence among workers, and encourage societal openness to change.

For us innovators, the best thing we can do is keep striving to improve people’s lives and do what we do best: innovate.

Stay tuned for part 2, in which we’ll look at Philippe Aghion and Peter Howitt’s contributions, including the concept of creative destruction.