Deep-Fried Turkey: A Thanksgiving Innovation Story

By Mike Rainone

On Thanksgiving, Donna and I typically do four turkeys, all deep-fried. We used to do one regular, oven-cooked turkey to get dressing, but who needs dressing when you can have more deep-fried turkey instead? The only downside to deep-fried turkey (besides the Darwin Awards folks who manage to blow things up) is how expensive the peanut oil is—$50 for three gallons of oil is outrageous.

Still, it’s worth it, because those turkeys are the best-tasting thing on the planet—crispy and juicy and packed with flavor. Each year, the vultures (a.k.a., my loving family) descend and pick apart the birds. By dinner, only one turkey survives.

Deep-fried turkey has become a Thanksgiving necessity in our house, but this style of cooking didn’t always exist. What is now tradition was once innovation.

Over the past couple of decades, deep-fried turkey has amassed a cult-like following. It has nearly made its way to the North Pole, thanks to our son, who took it to the far north country, where it has been widely adopted.

As far as innovations go, it’s been wildly successful. So in celebration of the holiday, let’s take a look back at how this innovation came to be and what allowed it to take off.

Cajun Roots: From Boiled Crawfish to Deep-Fried Turkey

If Donna and I are lucky and get any turkey leftovers after the vultures have left, I make turkey terazzini, and Donna uses the bones to make broth for gumbo. This is fitting, because the idea to deep-fry turkeys came from Cajuns in Louisiana.

It all started with the popularization of butane camp stoves back in the 1940s. By the 1970s, some Cajun innovators had the idea to adapt these camp stoves to make a favored delicacy: boiled crawfish. They rigged up a large aluminium pot to a gas burner, creating a portable way to cook crawfish. You could pull the crawfish from the water and plop them straight into the pot right there.

Before long, cooks realized that they could use the pots for more than just boiling crawfish. They started using the rigs to fry fish and chicken as well. From there, the jump to turkeys was inevitable.

It’s a tale as old as time in innovation: start with something that already exists, like a butane camp stove, and repurpose it to solve a different problem.

“The Ultimate Insult to Wholesome Food”: Overcoming the Critics

In the 1980s, newspaper articles about deep-fired turkey began to spread. (I miss the days when deep-frying turkeys was considered news!) While some were intrigued by the novelty, others were appalled, including the National Turkey Federation. They sent out a press release titled “Deep-Fried Turkey!!! The Ultimate Insult to Wholesome Food” in which they said eating fried turkey was like “staring into a loaded double-barrel shotgun. One barrel is a cardiologist's nightmare, the other … is a microbiologist's worst dream come true."

Critics also voiced concerns over safety. In 1984, the New Orleans Times-Picayune food editor Dale Curry published a recipe for deep-fried turkey after interviewing restaurateur Jim Chehardy, who claimed, “You’re never going to bake another turkey after tasting this.”

As Curry put it, after publishing the recipe, “By nightfall I had become known as the first food editor to burn down two houses … In writing that first recipe, so tedious as it was, calling for a horse syringe and plastic rope, I managed to leave out one detail -- DO NOT COOK NEAR THE HOUSE. So I was watching the evening news that Thanksgiving night and a New Orleans resident with house flaming behind him told a TV news reporter, 'I'll never use another one of those recipes.' (I silently thanked him for not mentioning my name or publication.)"

And yet, over the following years, the Times-Picayune's most-requested recipe was that for deep-fried turkey.

In 1987, Curry asked Chehardy to demonstrate the method for 110 members of the Newspaper Food and Writers Association (now the Association of Food Journalists). The innovation really started to take off then. By the 1990s, it had made its way to Martha Stewart Living and the New York Times, and today, the National Turkey Federation features multiple recipes for deep-fried turkey on their website.

Innovations often face resistance from the general public and entrenched experts, but by enlisting a small, dedicated group of first adopters, you can push back against the status quo.

Mass Appeal through Micro Inventions

The first deep-fried turkeys were jury-rigged affairs, using crawfish or gumbo pots, DIY harnesses made from nylon rope, and, as Curry noted, horse syringes to inject the turkey with marinade. For the average home cook, this made deep-frying a turkey a daunting task. As the method gained popularity, though, specialized equipment was invented to make it safer and easier.

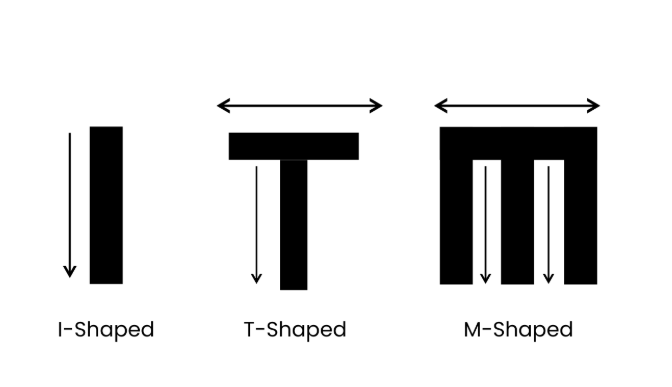

In our last blog, about Joel Mokyr’s work detailing the requirements for sustained growth (which earned him the Nobel Prize), we discussed micro inventions, which are the incremental improvements that build upon what exists to create something new and better. Deep-frying turkeys was the macro invention, and the micro inventions built atop it helped the practice achieve wider appeal.

For example, perforated inner baskets and lifting hooks replaced the need for DIY rope harnesses, which made inserting and removing the turkey far simpler. Injector syringes were created specifically for turkeys and were more accessible than horse syringes for many. Thermometers were built directly into turkey fryers to make monitoring temperature easier, with some fryers including automatic shutoff if the temperature gets too high. Today, there are even oil-less “fryers” that use infrared heat to mimic the effects of a deep-fried turkey without using oil.

Even with an innovation that seems relatively simple, like deep-frying turkeys, there are often dozens of micro inventions stacked together to make it a commercial success. It’s not just about creating something new, but about making the “new” better.

A Feast of Innovation

The story of the deep-fried turkey is a perfect reminder that innovation rarely happens in a vacuum. It began with an existing technology (the butane camp stove), was sparked by an unrelated need (boiling crawfish), faced fierce resistance from established institutions (the National Turkey Federation), found a following among culinary enthusiasts, and achieved mass market success through iterative improvements—the micro inventions that made the process safe and accessible.

Whether you’re celebrating with a classic oven-roasted bird or a crispy, deep-fried masterpiece this year, take a moment to appreciate this simple truth: every tradition was once an innovation. The most successful innovations, like the deep-fried turkey, are those that solve a problem (dry turkey!) in a unique way and become so good they can’t be ignored.

From all of us at PCDworks, we wish you a safe, delicious, and innovative Thanksgiving.