A Cognitive Psychology Technique for Better Innovation: Unlock Wisdom with the Nomological Network

I am first and foremost an epistemologist, which means I’m interested in the study of knowledge and the all-important question: “How do we know what we think we know?”

There’s a great joke about epistemologists that goes like this:

While on a trip to Scotland, an engineer, a physicist, and an epistemologist spot a black sheep.

“Look!” the engineer says. “The sheep in Scotland are black!”

“No, no,” counters the physicist. “At least one sheep in Scotland is black.”

The epistemologist considers for a second, then says, “Well, at least one sheep is black on one side.”

Maybe epistemologists aren’t the most fun at a dinner party, but they’re great when it comes to problem-seeking, because they avoid jumping to conclusions.

Jumping to conclusions is one of the biggest issues in problem-seeking, so we can learn a thing or two from epistemologists. Specifically, we can use the concept of a nomological network to help dig past surface-level knowledge and reach greater understanding, which will lead to more effective innovation.

What is a Nomological Network?

Nomological network is a term from cognitive psychology. Courtesy of Wikipedia, it is “a representation of the concepts (constructs) of interest in a study, their observable manifestations, and the interrelationships between these.” A nomological net might look like this:

In psychology, the purpose of a nomological net is to demonstrate construct validity, or how well a test/study measures the construct (a concept that cannot be directly observed or measured—e.g., conscientiousness or self-esteem) it was designed to evaluate.

More simply, for our purposes, a nomological net is a way to view the layers of information. The purpose is to help you move from surface-level truths (observations) to deeper-level truths (constructs), while also seeing the interrelationships between the observations and constructs.

Often, in problem-seeking, what we come up with are just excuses, meaning a justification without clear evidence for the validity of the attribution. What we need are explanations: valid attributions. This is what a nomological net can help us reach.

Let’s look at a simple example. Say you have a friend who is very anxious, and he claims, “I’m this way because my mother dropped me on my head.” He is attributing his behavior to his recollection that his mother dropped him on his head.

Is that what’s really causing the behavior? Maybe. Maybe not. Right now it’s just an excuse for his behavior, because we have an observation that he believes to be true (his mother dropping him on his head), and he is attributing his behavior to that with only recalled evidence. Before we make a conclusion, let’s gather more observations. Was the friend dropped on his head accidentally, or was he abused? Were there other incidents besides being dropped on his head? Let’s say yes. Now we’re starting to build a nomological net and getting a fuller picture of the truth.

We could build this out even further. For example, maybe the friend had untreated dyslexia and was belittled every time he did poorly in school, which could lead to another construct of “low self-esteem” that also impacts his anxiety today. For now, you get the point: a nomological net is a way of mapping out everything you know so that you get a fuller, more nuanced understanding of the situation.

How Can We Use a Nomological Net in Innovation?

Okay, so now let’s look at how we can apply a nomological net to innovation. We’ll use the Chrysler minivan as an example.

Before creating the minivan, Hal Sperlich and his team conducted many interviews with customers to identify problems. One of the things many people said was that sedans were too cramped when traveling with their kids. If we stopped at that surface-level truth, then we would come up with an excuse: sedans aren’t big enough. So then our solution likely would’ve been to make a bigger sedan. Not very innovative.

Let’s dig deeper with a nomological net, laying out all the common complaints people gave to Sperlich and his team:

Now we have a much more complete picture. We can see all of the problems customers have and how they’re related. The fact that vans are awkward to drive is part of why they’re so challenging to park. While customers want more space, when space increases, maneuverability is impacted. Likewise, accessibility is affected by space as well.

I have no idea whether Sperlich and his team used a nomological net, but I bet they did something similar, even if they didn’t have the psychological term for it. They looked at all the information to figure out the true problem. The deeper-level problem wasn’t that sedans were too small or that vans were too cumbersome. It was that current vehicles did not meet customers’ needs. They needed an entirely new vehicle—not a car or a van. A minivan, a hybrid between car and van.

Knowledge to Understanding to Wisdom

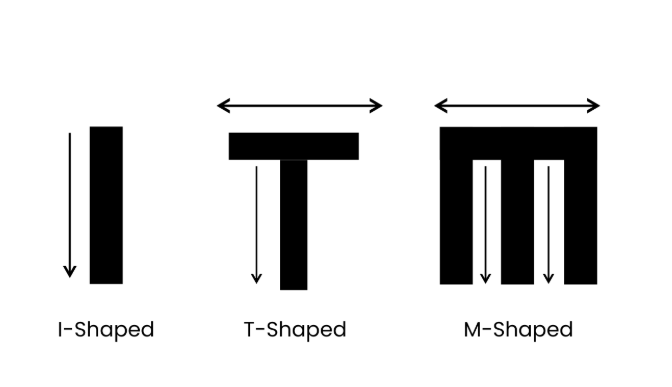

A nomological network is a tool for innovation, and like most things in innovation, it goes back to the fundamental idea of knowledge, understanding, and wisdom.

Observations can become knowledge. They’re the facts about the problem—e.g., “I know” loading things in and out of a car is a pain.

Constructs represent understanding. You derive constructs by integrating the knowledge into a whole that makes sense and allows you to make decisions (predictions) from that understanding—like the need for space, accessibility, and maneuverability.

Wisdom is how you apply the nomological map in the real world, leveraging your understanding (both the explicit knowledge that you have gained from the immediate problem analysis and the tacit knowledge that you have accumulated over the years) to find insights and make smart decisions. Wisdom is taking everything customers said and deciding to build a minivan, even though no one explicitly asked for it.

Knowledge to understanding to wisdom: this is the most important secret of innovation. If you can get this right, everything else falls into place more easily. So if you find yourself getting stuck in surface-level knowledge, try using a nomological net to dig deeper to wisdom.